Search Results for: '{{searchText}}'

Sorry...

We don't seem to have what you're looking for.

However we do have thousands of magnificent pieces of silver and jewellery available for you to view online. Browse our store using one of these categories.

Please wait for loading data...

Browse these categories under "Russian Silver"

_1919_general.jpg)

Russian Silver and Polychrome Cloisonne Enamel Candlesticks - Antique 1891

Price: GBP £8,950.00Russian Silver Gilt and Polychrome Cloisonne Enamel Spoons - Vintage Circa 1945

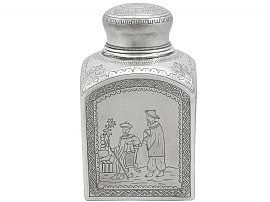

Price: GBP £5,445.00Russian Silver Tea Caddy - Antique 1890

Price: GBP £2,695.00Russian Silver Gilt and Niello Enamel Beaker - Antique 1827

Price: GBP £1,975.00Russian Silver Gilt and Enamel Vodka Tots - Antique Circa 1890

Price: GBP £1,895.00Russian Silver Spice Box - Antique 1854

Price: GBP £1,755.00Russian Silver & Niello Enamel Beaker - Antique 1839

Price: GBP £1,645.00Russian Silver Gilt Egg Cups - Antique Circa 1890

Price: GBP £1,645.00Russian Silver Egg Cups - Antique Circa 1900

Price: GBP £1,645.00Russian Silver Gilt and Polychrome Cloisonne Enamel Napkin Ring - Antique Circa 1915

Price: GBP £1,445.00Russian Silver Shoe Vesta Case - Antique Circa 1855

Price: GBP £1,425.00Russian Silver 'Boot' Vesta Case and Taper Holder - Antique Circa 1855

Price: GBP £1,425.00Russian Silver Egg Cups - Antique Circa 1905

Price: GBP £1,425.00Russian Silver and Niello Enamel Beaker - Antique 1865

Price: GBP £1,425.00Russian Silver Gilt and Polychrome Cloisonne Enamel Sugar Basket - Vintage Circa 1970

Price: GBP £1,315.00Russian Silver Gilt and Polychrome Cloisonne Enamel Tea Strainer - Vintage Circa 1970

Price: GBP £1,145.00Russian Silver Basket - Antique Circa 1900

Price: GBP £1,145.00Russian Silver Kiddush Cup / Beaker - Antique 1889

Price: GBP £995.00