Scottish Silver

Antique and Vintage Scottish Silver for Sale

Explore our fine collection of antique and vintage Scottish silver for sale. Our collection includes Scottish silverware from the Victorian and Georgian periods and often crafted by collectable silversmiths of the period.

All silverware purchases at AC Silver include a complementary insurance valuation and free global shipping.

Andrew Campbell, using his 40 years’ experience within the antiques industry, handpicks all Scottish silver for sale.

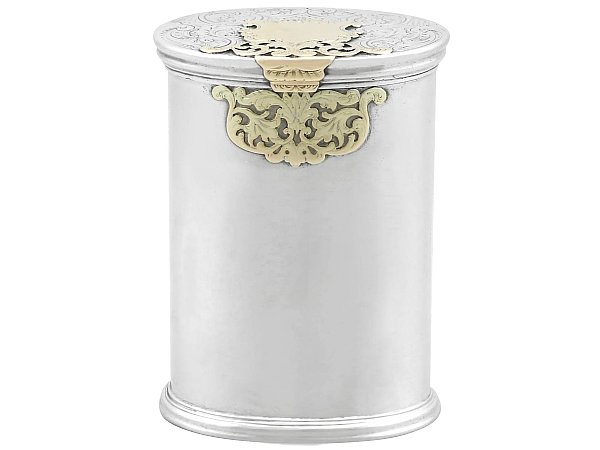

Distinctly Scottish silver was primarily plain, with very little in the way of decoration. This is reflective of the economy in 18th century Scotland. For most, silver was a commodity that could act as a handy cash reserve. The emphasis was to create something from the silver itself, rather than using the silver to add embellishment.

Scottish Silver Frequently Asked Questions

Quaich

The Quaich is an item known as Scotland’s ‘Loving cup’ or ‘Cup of Friendship’. The word Quaich comes from the Gaelic word ‘cuach’, meaning cup. A traditional element of Scottish silver, the quaich is a shallow cup, with two handles on opposite sides which were carved out of wood or imitation scallop shell. Larger quaiches were also produced for the purpose of drinking ale. The quaich originated in the Highlands, and was first produced in the 17th century. They were originally crafted from wood but later were made out of silver, brass and pewter. The varying materials adhered to the fashions of the upper classes of northern Scotland. The centre of the bowls could often be engraved with ‘SGUAB AS I’ which means ‘Toss it back’ and, as the name suggests, the quaich was used to offer a welcome drink at gatherings whether that be clans, weddings, christenings or to welcome friends into the home.

Bullet Teapot

The bullet teapot was another popular item often crafted in Scottish sterling silver. Bullet teapots have a spherical form, and are mounted on a footing. They were popular during the Georgian period, with some of the finest examples being made by William Ayton and Edward Lothian.

Thistle Cup

Another piece of typically Scottish silver is the thistle cup. These cups were most commonly made around the turn of the 18th century. A bold usage of calix strap work ornaments the lower border of the cup. The effect created here resembles the Scottish wilderness in which the famed flower thrives.

Spoons

The hash spoon is a serving spoon, normally 30-40 cm long, used to serve meat and potatoes.

There is also the disc-end spoons that were produced predominantly in Scotland from the 1500-1600s. The design of this spoon was more advanced than spoons being created in England at the same time.

Despite Edinburgh and Glasgow housing the main assay offices, it was not often that silversmiths actually sent their items to either of these cities to be hallmarked. Consequently, many items were only marked with the maker’s initials and with the town the item was crafted in. This was generally in order to avoid the duty charge which was re-imposed in 1784. These provincial marks grew less common after 1860, rendering provincial Scottish silver quite collectable.

There was a much wider area of manufacture in Scotland than in England, and therefore many hallmarks for smaller areas. Some provincial hallmarks include:

- Perth: Lamb and flag, the sign of St. John

- Aberdeen: ADD

- Elgin: ELN

- Banff: BA

- Inverness: INS, or a mark of a camel